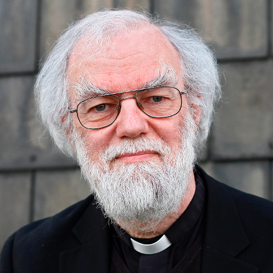

Rowan Williams, Archbishop and Theologian

Dates: 1950-present

Location: Wales; England

Context: Rowan Williams is a Welsh Anglican bishop and theologian who served as Archbishop of Canterbury from 2002 to 2012. He was born in 1950 to Welsh-speaking parents. Williams was a devout Christian and gifted student from his youth. He studied theology at Cambridge University, then completed a doctorate in theology at Oxford University. He trained for the ordained ministry at the College of the Resurrection in West Yorkshire. He was then ordained deacon and priest in the Church of England. In the years following, Williams split his time between parish ministry and academia, eventually becoming Distinguished Professor of Divinity at Cambridge. A multi-talented person, he published several books of theology and poetry; in later life, he also wrote a play about the life of Shakespeare. Williams was consecrated Bishop of Monmouth in the Church in Wales, and then Archbishop of the Church in Wales. Increasingly he became known as a Christian intellectual who could speak eloquently on social issues. His appointment as Archbishop of Canterbury was the first time in the modern era a cleric was appointed to that position from outside the Church of England. During Williams’ archiepiscopate, the Anglican Communion almost fractured over issues like the ordination of women as bishops and same-sex marriage. Williams tried to keep all sides talking to each other and to find a way forward for the Communion, but solutions proposed during his tenure were not entirely successful. He stepped down as Archbishop of Canterbury in 2012, and since then he has continued to publish theology and poetry. In his book Being Christian, Williams gives an insightful examination of the implications of Christian baptism.

Excerpts from Being Christian: Baptism, Bible, Eucharist, Prayer (2014):

“To be baptized is to recover the humanity that God first intended. What did God intend? He intended that human beings should grow into such love for him and such confidence in him that they could rightly be called God’s sons and daughters. Human beings have let go of that identity, abandoned it, forgotten it or corrupted it. And when Jesus arrives on the scene he restores humanity to where it should be. Jesus has come down fully to our level, to where things are shapeless and meaningless, in a state of vulnerability and unprotectedness… This suggests that the new humanity that is created around Jesus is not a humanity that is always going to be successful and in control of things. It means you might expect to find Christian people near to those places where humanity is most at risk, where humanity is most disordered, disfigured and needy. If being baptized is being led to where Jesus is, then being baptized is being led towards the chaos and the neediness of a humanity that has forgotten its own destiny.

If all this is correct, baptism does not confer on us a status that marks us off from everybody else. To be able to say, ‘I’m baptized’ is not to claim an extra dignity, let alone a sort of privilege that keeps you separate from and superior to the rest of the human race, but to claim a new level of solidarity with other people. It is to accept that to be a Christian is to be affected – you might even say contaminated – by the mess of humanity. The gathering of baptized people is therefore not a convocation of those who are privileged, elite and separate, but of those who have accepted what it means to be in the heart of a needy, contaminated, messy world. To put it another way, you don’t go down into the waters of the Jordan without stirring up a great deal of mud!

Discussion Questions:

- In what ways do we let go of, forget, or abandon our intended identity as sons and daughters of God? What would it look like to reclaim that identity?

- Does the fact that you are baptized affect your daily life? How does being baptized change the way you think, speak, or act? How should it change those things?

- How can we be reaching out and helping others “in the heart of a needy, contaminated, messy world” when we are not able to be around others? What does the baptismal solidarity Williams describes look like in a time of social distancing?

Comments are closed.